22 April 2025

“Perhaps my best years are gone. When there was a chance of happiness. But I wouldn’t want them back.

Not with the fire in me now. No, I wouldn’t want them back.”

In 1998, Sir Ian McKellen caused a sensation in Yorkshire when he abandoned London and decamped to the West Yorkshire Playhouse (now Leeds Playhouse) to lead a company of actors and star in three productions: as Dr. Dorn in Chekov’s The Seagull, Prospero in The Tempest and as the star of Noël Coward’s Present Laughter. All shows sold out immediately and proved to be much needed shot of star power adrenalin for the local theatre scene.

Now another Hollywood star in the shape of Gary Oldman – the recipient of an Oscar, a Golden Globe and three BAFTAs, and whose films over a 40-year career have grossed over $11 billion worldwide making him one of the highest-grossing actors of all time – has done the same thing for the city of York as a theatrical fundraiser.

After co-writing the pilot for a TV sitcom set in a British regional theatre with his wife, it seems that Gary was lured once more by the smell of the Lichner greasepaint and roar of the crowd to be back on stage after many decades away. His return to York Theatre Royal, where he made his acting debut in 1979 in Thark (and then appeared as Puss in Dick Whittington and His Cat!), straight from drama school, finds him starring in Samuel Beckett’s 1958 one-man play, Krapp’s Last Tape. And the appearance of the star of the smash-hit Apple TV+ spy series Slow Horses, has proved to be theatrical Viagra at the box office, where tickets are now as rare as hen’s teeth.

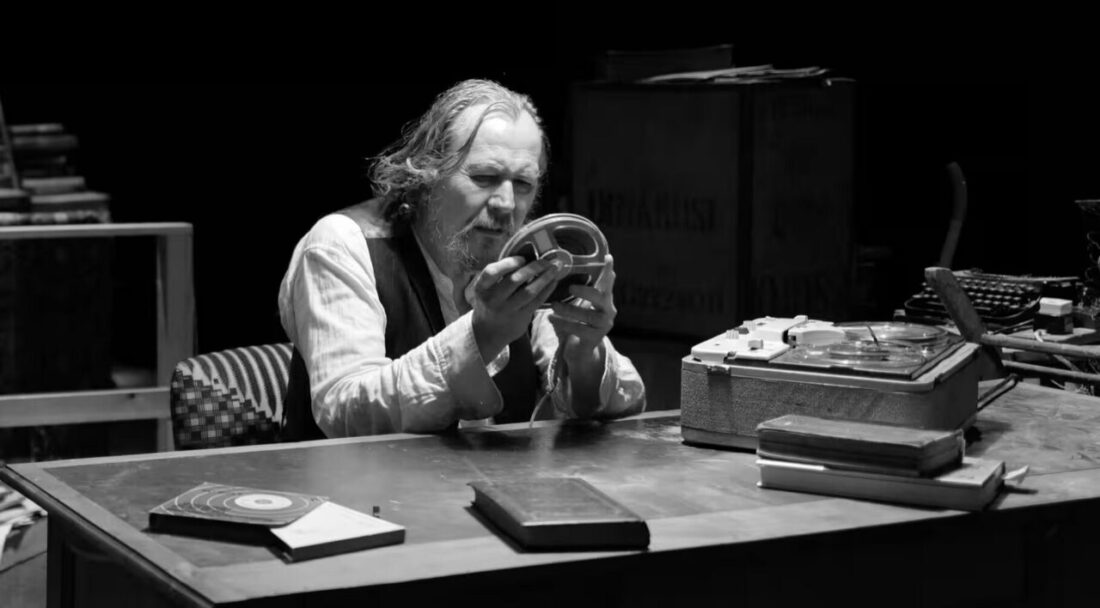

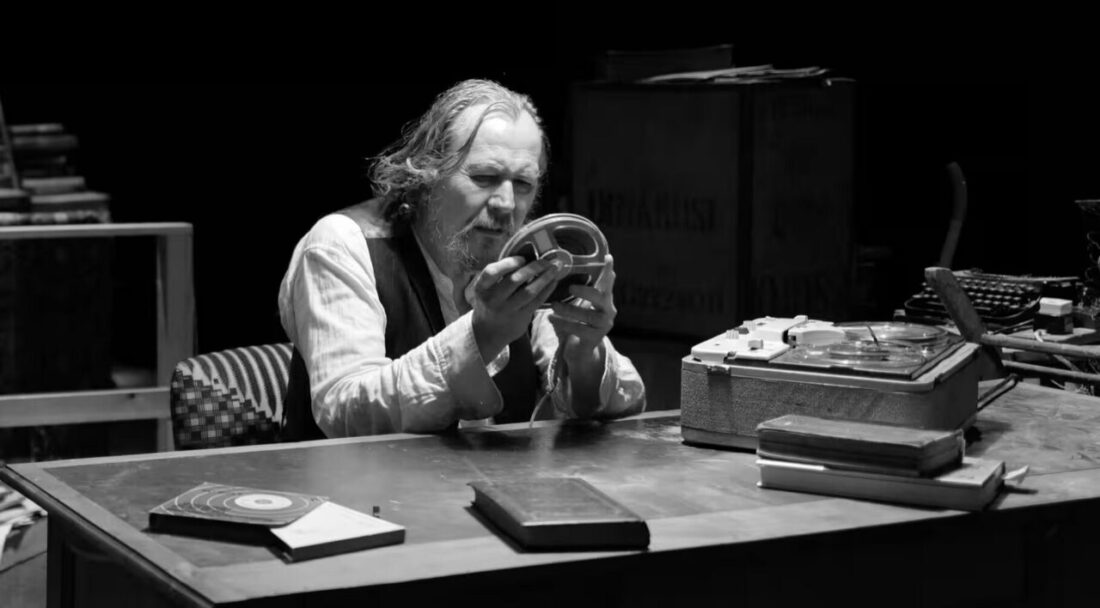

Every year on his birthday, a man named Krapp records a new reel-to-reel tape reflecting on the past year. On his 69th birthday, Krapp, now a lonely man, is ready with a bottle of booze, several bananas and his trusty tape recorder. Surrounded by mountains of junk – what looks like the detritus of his life (set design by Mr Oldman), he listens back to a recording he made as a young man in his 20s, and must face the hopes of his past self head on.

Originally entitled Magee Monologue, Krapp’s Last Tape was inspired by Beckett’s experience of listening to Irish actor Patrick Magee read extracts from Molloy and From an Abandoned Work on the radio – he loved his voice so much. Krapps’ Last Tape, a potent and beguiling mix of pain and past happiness, grief and lyricism, has over the decades since attracted some of the greatest actors of our age to play Krapp, from Michael Gambon, Albert Finney (miscast at 37, he was absurdly young to play the role) and John Hurt to Stephen Rea and Richard Wilson. Playwright Harold Pinter was forced by illness to play him in an electrified wheelchair.

One of the earliest examples of a sound installation and coming five years after the West End success of Waiting for Godot opened up a glittering career in theatre for its author, the script is famously short – only a few pages long but including voluminous stage directions that the Beckett estate rule must be obeyed to the letter. Between the taped reflections and Krapp’s live dialogue – at times vague, at times vividly evocative – the play is, in the hands of a gifted actor, the Hamlet of monologues, and a tour-de-force.

“Just been listening to that stupid bastard I took myself for thirty years ago, hard to

believe I was ever as bad as that. Thank God that’s all done with anyway.”

So how does Mr Oldman hold up to previous Krapps? In truth he carries the burden of his past life lightly and has a wistful, grumpy delivery, taking little pleasure in the oft repeated recollection of love-making:

“I lay down across her with my face in her breasts and my hand on her.

We lay there without moving. But under us all moved, and moved us,

gently, up and down, and from side to side.”

He’s still finding his feet, with a couple of fluffed sound and lighting cues at the performance I attended on Saturday. Mr Oldman is wearing 3 hats: Actor, Set Designer and Director and in my opinion that’s one too many. A critical outside directorial eye would have sharpened and focussed his performance, and given it it the steely edge that it is sorely missing.

Many in the audience looked bemused at the play’s melancholic conclusion – it’s not an easy play to navigate and enjoy – and robbed of the chance of greeting the star on his arrival on stage with Broadway-style applause by messages on TV screens as they entered the auditorium, they gave him a warm, if polite rather than ecstatic reception at the end. For many, just for turning up I suspect.